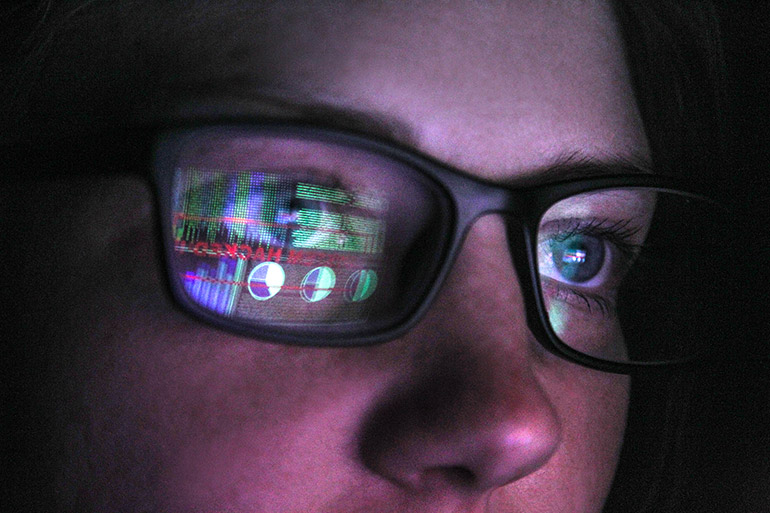

New UBCO research shows that over time, attempts to deceive others may become self-deception.

Eventually it becomes hard to distinguish between fact or fiction

The telling of lies might be just a bad habit for some, but a UBC Okanagan researcher says that over time lies will infiltrate a person’s memory for the truth.

Dr. Leanne ten Brinke is an assistant professor of psychology at UBCO and director of the Truth and Trust Lab in the Irving K. Barber Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences. She recently published research on how telling lies, and receiving feedback that the lie was believable, can impact people’s memory for the truth.

Her study, published in Memory, involved participants who were asked to file an insurance claim regarding a theft from an office. Some of the 140 participants were asked to lie and increase the number of items they claimed were stolen. Others told the truth. During a follow-up interview two weeks later, those who had lied could remember how many items had been stolen, but most liars had trouble remembering which items were actually taken and which they had fraudulently claimed stolen.

“The same as truth tellers, the liars correctly reported that four items were stolen,” Dr. ten Brinke says. “But when asked to list what was missing, most of the liars incorporated at least one of the items they lied about into their memory. The fictional piece became part of their memory.”

Dr. ten Brinke has spent much of her career researching liars and the art of deception. She admits the type of lie told in this research might be particularly vulnerable to distortions of memory because the lie only alters the presence or absence of an item — not quite the same as confabulating an entire story or deception.

In other words, the perceived and relative characteristics of the truthful and deceptive details are very similar, potentially accounting for the high number of dishonest participants who made a mistake — falsely remembering that one of the items they lied about had been stolen when it had not.

Over time, attempts to deceive others may become self-deception, she says. And it evolves as to how someone remembers a particular event. Lies, therefore, become part of your memory for the truth.

“Once the false detail is incorporated into memory, sharing that information no longer fits the definition of deception — because you’re not intentionally misleading anyone. You think it’s the truth, even though it’s not an accurate depiction of past events,” she says. “At some point, you knew it was a lie but now it’s been incorporated into your memory and you believe it to be true.”

Dr. ten Brinke describes deception as the art of “pulling the wool over someone’s eyes” and some people become quite skilled at the telling of lies. Sometimes, it’s a case of having time to practice. She says the more time a person has to practice the lie, the better they become at convincing others that it is true.

In other cases, self-deception may aid the liar. They can convincedly tell the lie because to them the distorted memory is perceived to be truthful.

“We would like to do future research to see how self-deception might improve your ability to dupe others,” Dr. ten Brinke adds. “There may be a perceived genuineness of that recollection. Where fiction has indeed become fact in your memory.”

About UBC's Okanagan campus

UBC’s Okanagan campus is an innovative hub for research and learning founded in 2005 in partnership with local Indigenous peoples, the Syilx Okanagan Nation, in whose territory the campus resides. As part of UBC—ranked among the world’s top 20 public universities—the Okanagan campus combines a globally recognized UBC education with a tight-knit and entrepreneurial community that welcomes students and faculty from around the world in British Columbia’s stunning Okanagan Valley.

To find out more, visit: ok.ubc.ca